Surviving the Wild

City folks learn primitive skills

By Curtis Wackerle of The Montana Standard. Photography by Meghan Brown. 09/12/2004

As the sun sets behind the Tobacco Root Mountains, and the temperature lowers into the 40s, Thomas Elpel, left, his nine-year-old son, Donny, his 15-year-old daughter, Felicia, and one of Elpel's two interns, Norm Grondin, gather around a fire built inside their wickiup, a tepee-like shelter made of logs, sticks and other forest deadfall. For thousands of years, man has used fire, and on this August night, the group's fire was made in the method of their ancestors long ago - with two sticks in a method called handdrill. Clothed in buckskins, the group, which also includes intern Brian Sechel, is camping for the night to practice primitive living skills. |

For more than one week, they did not brush their teeth. But don't worry, they found twigs to chew on. They say chewing on twigs helps keep the mouth clean, especially when you are not eating much sugar.

And anyway, bringing along a tooth brush and toothpaste on this trip would be cheating.

Dental hygiene is just one of the modern habits that Tom Elpel of Pony and his interns, Norm Grondin, 22, a Canadian from Windsor, Ontario, and Brian Sechler, 26, of New York City went without as they participated in a float trip on the Kootenai River in northwestern Montana in late August. The trip was designed to test the "primitive living skills" that Grondin and Sechler have traveled thousands of miles and dedicated six months of their lives to learn.

For tens of thousands of years, humans survived only because they were able to take their basic needs - food, clothing and shelter - from their immediate surroundings, usually with little more technology than their own hands. Proponents of primitive skills believe that by continuing to practice these basic skills, even if on a smaller scale than our ancestors, humans will have a better understanding of their world and will be able to live more harmoniously in it.

"I'm not saying everyone should live in a tepee," but the process of trying to be more connected to nature is what counts, Sechler said.

He and Grondin arrived in Montana at the beginning of April and will remain here through the end of September. For the last four months, they have been living in Silver Star, a community 15 miles south of Whitehall, in a trailer near a grocery store that Elpel owns, honing their primitive skills. Their six-month internship cost them each about $200 for food, lodging and raw materials.

Both interns said that a desire to be more comfortable in the woods and to transcend the often soulless modern world drove them to Elpel and Montana.

Both interns said that a desire to be more comfortable in the woods and to transcend the often soulless modern world drove them to Elpel and Montana.

"I always felt a little held back (in the woods) because I couldn't really merge with the environment," Sechler said. "I am used to walking into the woods, but having my body draw me back because I can't feed myself or keep myself warm."

Elpel's primitive skills internship intends to change all that.

Elpel's primitive skills internship intends to change all that.

"It's a unique thing they are experiencing," Elpel said. "They come from the city, and they end up as mountain men."

Both interns found Elpel through the Internet, where his Web site, www.hollowtop.com, serves as a marketplace for his books and videos about botany and primitive skills. It also contains information on a number of Elpel's projects to increase advocacy for much of Montana's public lands, particularly in the Three Forks area.

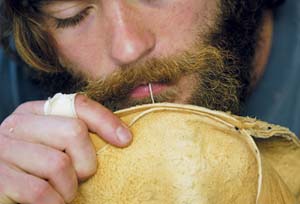

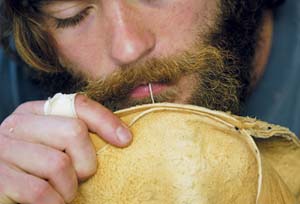

The interns' main tasks have been tanning deer and elk hides to make clothing and blankets, learning to start fires with friction, making deer jerky and learning about other foods that will sustain them for extended treks through the woods.

"I never thought I'd wear the skin off the tips of my fingers," Grondin said. He experienced this while scraping epidermal layers off hides, a step in the tanning process.

Grondin and Sechler said it is fulfilling to learn these ancient skills because it is a way to interact with nature that most people will never know. It is sad to see so much of humanity cast aside these skills so quickly, Grondin said.

Grondin and Sechler said it is fulfilling to learn these ancient skills because it is a way to interact with nature that most people will never know. It is sad to see so much of humanity cast aside these skills so quickly, Grondin said.

"Those skills took tens of thousands of years to perfect, and now they are going the way of the dinosaur," he said.

Elpel and the interns also spent the weeks prior to the Kootenai trip preparing the food that will sustain them in the wilderness. They ate deer jerky for protein, cattail flour for carbs. One primitive favorite is called an ash cake. This is cattail flour mixed with water and formed into a little ball. The ball is roasted over the open flames for crispiness.

With all the hiking and camping, Grondin and Sechler have become accustomed to sleeping on the ground. Even in Silver Star, no beds are to be found where they live.

With all the hiking and camping, Grondin and Sechler have become accustomed to sleeping on the ground. Even in Silver Star, no beds are to be found where they live.

"Beds are for suckers," Grondin exclaimed.

Living in Silver Star with its population of less than 100 has been quite the change of pace for the two, but the setting is just right for the experience, they both agree.

"I can feel very alienated in a city," Grondin said. Boredom prevails when minimal work is required to secure the basic needs that don't come quite so easy in the woods, he said.

"I can feel very alienated in a city," Grondin said. Boredom prevails when minimal work is required to secure the basic needs that don't come quite so easy in the woods, he said.

"A lot of it makes me sort of sad," Grondin said. "I see a lot of disassociation and unhappiness" in the modern world.

If nothing else, the six-month internship has allowed Grondin and Sechler to take a step back from that modern world and find a little inner peace in the Rocky Mountains.

-Sidebar-

Teacher practices what he preaches

Although primitive skills teacher Tom Elpel spent 12 years of his childhood in what would become the Silicon Valley in California, he had family in Montana and moved here as an adolescent.

He credits his grandmother with setting him on the path that would one day lead him to be a primitive skills mentor. At a young age, she began teaching him about edible plants, and his fascination with the natural world was tapped. At 16, he attended the Boulder Survival School in Utah where he learned many of the primitive survival skills he would eventually teach.

Elpel likens his primitive skills work to that of an anthropologist because it provides a fresh look at a culture, he said.

"It's not a way of life, but a way of looking at life," he said.

"It's not a way of life, but a way of looking at life," he said.

Apparently, he walks what he talks. Elpel's home in Pony is built of stone and log and uses solar power for heat and energy.

"I thoroughly enjoy not paying my power bill every month," he said.

Elpel hopes the economy of the future will model what he has done with his own home.

Elpel plans to focus future internships on the concept of "green business."

It's possible "to make a profit by making the world a better place," he said. |

Used with permission of the Montana Standard.

Go to Participating in Nature: Wilderness Survival and Primitive Living Skills

Go to Books and Videos by Thomas J. Elpel

Return to the Primitive Living Skills Page.

Both interns said that a desire to be more comfortable in the woods and to transcend the often soulless modern world drove them to Elpel and Montana.

Both interns said that a desire to be more comfortable in the woods and to transcend the often soulless modern world drove them to Elpel and Montana.  Elpel's primitive skills internship intends to change all that.

Elpel's primitive skills internship intends to change all that.  Grondin and Sechler said it is fulfilling to learn these ancient skills because it is a way to interact with nature that most people will never know. It is sad to see so much of humanity cast aside these skills so quickly, Grondin said.

Grondin and Sechler said it is fulfilling to learn these ancient skills because it is a way to interact with nature that most people will never know. It is sad to see so much of humanity cast aside these skills so quickly, Grondin said.  With all the hiking and camping, Grondin and Sechler have become accustomed to sleeping on the ground. Even in Silver Star, no beds are to be found where they live.

With all the hiking and camping, Grondin and Sechler have become accustomed to sleeping on the ground. Even in Silver Star, no beds are to be found where they live.  "I can feel very alienated in a city," Grondin said. Boredom prevails when minimal work is required to secure the basic needs that don't come quite so easy in the woods, he said.

"I can feel very alienated in a city," Grondin said. Boredom prevails when minimal work is required to secure the basic needs that don't come quite so easy in the woods, he said.  "It's not a way of life, but a way of looking at life," he said.

"It's not a way of life, but a way of looking at life," he said.