"How many a poor immortal soul have I met well-nigh crushed and smothered under its load, creeping down the road of life, pushing before it a barn seventy-five feet by forty, its Augean stables never cleansed, and one hundred acres of land, tillage, mowing, pasture, and wood-lot!"

-Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Wealth & Work

A Ten Thousand Year Old Pattern

By Thomas J. Elpel

Adapted from Green Prosperity: Quit Your Job, Live Your Dreams

When we think back to our ancestry in the stone-age we sometimes pity them; we pity the poor people who had it so rough that they had to work their every living moment just to find enough food to keep them alive. But ironically, our ancestors typically worked much less than we do today. They had less work, less stress and less depression. Indeed, it is sometimes said that you could hear the laughter of a native village from two miles away!

Anthropologists have documented that cultural advancements usually result in people working more, not less. For example, studies in the 1960's of the !Kung people, a hunter-gatherer society in Africa, showed that they worked roughly half as much as people in industrialized societies. The !Kung worked only about twenty hours per week, or three hours per day, for their subsistence. Their other chores, such as building shelters, making tools and cooking, added up to another twenty-some hours per week for a total of 40+ hours per week. By contrast, those of us in industrial cultures work about 40 hours per week at a job and 40 hours more at home and after work (commuting, shopping, cooking, washing, cleaning, fixing), for a total of roughly 80 hours per week.

The Shoshone Indians, once a hunter-gatherer culture in the Great Basin Desert, had a life-style that was probably similar to that of the !Kung people. Observers from our own culture in the 1800's often called the Shoshone lazy because they never seemed to work. They were not lazy; they just did not need to work. They carried everything they owned right on their backs, and it did not take them long to manufacture such a small quantity of material goods. Their life-style simply did not require them to work all the time.

Understanding these relationships between material goods or "wealth" and the work it takes to produce it is crucial to the effort of gardening the economic ecosystem to produce a life of health and abundance, both for ourselves and for the planet.

Do not be mistaken into thinking that hunting and gathering is an efficient way to earn a living. I know from firsthand experience because I've spent a large part of my life learning and teaching stone-age living skills. A hunter-gatherer typically harvests only two or three calories of food for every calorie expended. By contrast a farmer with an ox and plow can grow and harvest about thirty-three calories for each calorie expended. A modern American farmer can produce 300+ calories of food for each calorie of body energy expended. This might be easiest to think of as plates of food. For every plate of food consumed, the hunter-gatherer harvests 2-3 new plates full, the ox and plow farmer harvests 33 plates full and the industrial farmer harvests 300 plates full. Granted, industrial farming consumes vast quantities of fossil fuels to produce those 300 plates full of food, and that is an important subject we will return to. The purpose for now is to understand that with the aid of technology and energy we've been able to greatly increase the level of production per person.

Ultimately, the people of a hunter-gatherer society work less only because they produce less material wealth than people of other cultures. To understand this better, consider the wild animals. Think about deer, or birds, or coyotes, for instance. Have you ever seen or heard of an animal dying from hypertension, or getting ulcers from work stress? Probably not. You might see them forage intensively for a few hours, or they might nibble away all day, but rarely do you see them foraging frantically just to stay alive. They spend much of their time wandering, playing, or basically just "hanging around". There is a certain efficiency to a life-style where, for the most part, the only job you ever have to do is to eat. Life was probably pretty casual for our ancestors before they learned to make tools.

The evolution of tools made our species more efficient, but it also meant we had to work more. As animals, all we had to do was eat, but with the arrival of the stone-age we also had to make tools, shelters, clothing, jewelry, dishes and gather firewood. The evolution of tools meant that we could spend less time actually foraging, but it meant that we spend more time dealing with all the new chores. Still, on the whole, work was not too demanding. With the continuing evolution of culture, however, we found ever more and more work to do. The evolution of farming gave us a new level of prosperity, but it also gave us more work. When we started living in one place we began building fancier, more permanent shelters, complete with furnishings. We started living in bigger groups, and we found a need for some form of government, such as a spiritual leader, to maintain the stability of the community. That meant that those of us who farmed had to contribute a share of the food we harvested as a sort of tax to feed this non-farming person. Originally we only had to harvest enough food for ourselves, but with the advancement of culture we suddenly had to harvest additional calories of food for other people, from leadership, to toolmakers to artists.

Imagine being a tailor, one of several within a simple economy. You custom-cut and hand-stitch garments to exchange for your food, shelter, and other needs. Like other local tailors, it takes you a week to make an outfit for one customer, so your total annual production is 52 complete outfits per year. Therefore, those 52 outfits are equal in value to everything that you trade for and consume within the year. But then you get this idea, "What if I could make a device to assist with the sewing, so that I could produce more garments in less time. Then I could sell more garments and make more money, or I could take extra time off to hike in the woods."

Imagine being a tailor, one of several within a simple economy. You custom-cut and hand-stitch garments to exchange for your food, shelter, and other needs. Like other local tailors, it takes you a week to make an outfit for one customer, so your total annual production is 52 complete outfits per year. Therefore, those 52 outfits are equal in value to everything that you trade for and consume within the year. But then you get this idea, "What if I could make a device to assist with the sewing, so that I could produce more garments in less time. Then I could sell more garments and make more money, or I could take extra time off to hike in the woods."

So, after completing each day's tailoring work, you tinker with gadgets until at last you have built a simple sewing machine. Soon you are producing three outfits per week, or 156 garments per year, and your customers are still paying what they used to. For awhile you are the richest person in town. You spend a little less time working and more time playing and shopping. But then two things happen to burst your bubble.

First, with the extra garments on the market, not all the outfits are being sold. But it cost you less to produce them anyway, so you lower the price a little bit, knowing that you can still make a fantastic profit. However, the other tailors have meanwhile noticed both your spendthrift ways and your lower prices. In order to stay competitive they also invent sewing machines, so that each tailor is now producing 156 outfits per year. But with so many garments on the market, the value has to fall. In the end you are producing more clothing, but making less profit per unit. That's good news for your customers, who previously could afford to own only two outfits at a time. Now they can afford three outfits, so consumption increases.

However, even with increased consumption, there are still too many garments on the market. A price war ensues until none of the tailors are making a profit at all. Finally, one of your competitors drops out of the business completely and finds a new line of work. That reduces the number of garments in production, allowing prices to rise somewhat, although never as high as before. Ultimately you are making the same income that you were before inventing the sewing machine, but now you have to produce 156 garments per year instead of 52!

Producing those extra garments isn't any more work than before, just a bit more complicated. You used to sit out on the front porch stitching away all day long, but that isn't an option any more. With the increased throughput you need to stay focused on the sewing machine, operating and maintaining it, plus you need to order more material and make more space for it. If the sewing machine breaks or the wrong kind of material arrives then you've got added stress, because you have to keep production up to make a living.

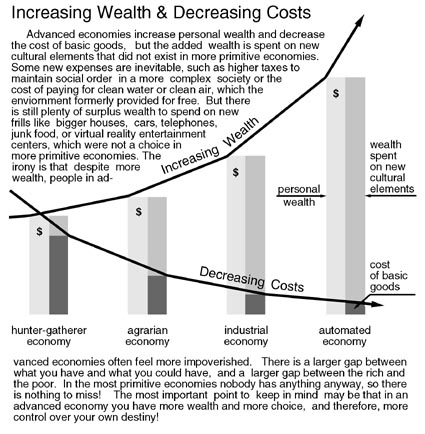

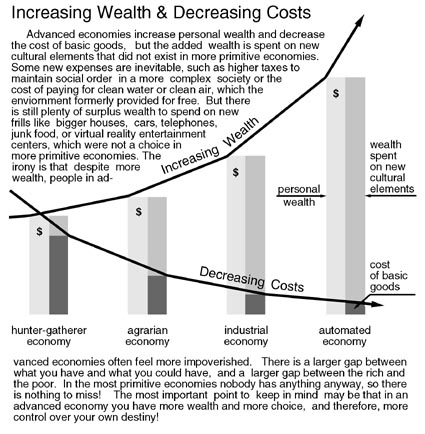

Despite increasing production and making the same income as before, you are still much better off. Because while you were increasing your production capabilities, so was the butcher, the baker, and the candlestick maker. Each of their industries experienced the same ups and downs as yours so that production increased, prices plummeted, and some of the competitors were forced out-of-business to seek other forms of work. Given the lower prices you are able to buy more meat and bread and candlesticks for your family, so you are ultimately producing more wealth and getting more wealth in return, even while your income is unchanged. You even have a little extra money to donate to a neighbor who is struggling. The accompanying graph illustrates the increasing wealth and decreasing costs in primitive and increasingly advanced economies.

But what about all those workers who were forced out of tailoring, meat processing, baking, and candlestick making? They are not needed in any of the traditional roles, so they ultimately create new niches in the marketplace. One starts a laundry service to help clean all those extra garments, and one becomes a carpenter to build closets to hold the extra clothes. Another invents the oil lamp and sells both the lamps and the oil, so that you can stay up later into the evening, visiting in the parlor or reading a new book-written by someone who coincidentally used to be a candlestick maker.

The community could not have afforded such extravagance before, but now, with increased production and lower prices, everyone has a little extra wealth to spend in new ways. Soon there is a new standard, so that bigger houses, freshly laundered clothes, reading entertainment and oil lamps are no longer extravagances, but "necessities" everyone must work for.

On top of that, with the increased production and consumption, there are new waste problems to deal with as well. As a tailor, you once put any scraps of cloth on your garden for mulch between the rows. But now you produce more waste than you can use, so it has to be hauled away at an extra expense. A service that was once handled for free by the environment is now an expense. Besides, with the cost of produce falling like everything else, it makes more economic sense to sew more garments and trade for your veggies than to grow them yourself, so you let the garden go by the wayside.

Ultimately you are significantly wealthier than before, but you are also working harder too. Nobody said you had to pay for oil lamps and oil or books and freshly laundered clothes, but you would feel deprived if you didn't, so you work a little harder to give your family all the good things that life has to offer. And then one day you get this idea, "What if I could make a better sewing machine, so that I could produce many more garments in less time. Then I could sell more garments and make more money, or I could take extra time off to hike in the woods."

As you may sense from this story of the tailor, the simple act of streamlining production efficiency has unintended consequences that reverberate throughout the economic ecosystem, ultimately changing an opportunity to make more money into a new standard for production and consumption that must be maintained just to stay even with middle-class society. Several points from this story deserve further emphasis, including that increased production 1) forces people out of old jobs to find new niches, but also makes us wealthier, 2) gives us more products and more freedom to choose, but also makes us work more, 3) results in a greater surplus to share with "non-producing" individuals such as government officials, nonprofit organizations, or the poor, 4) suggests that we will witness still more changes in the future, except 5) that increased production also seems to require increased throughput of materials and energy, and therefore causes greater ecological impact.

1) Increased production forces people out of old jobs to find new niches, but also makes us wealthier. At the beginning of the 20th century America was a nation of farmers, with most families producing enough food for their own consumption, plus a small surplus for trade. But industrialization of agriculture has allowed fewer and fewer farmers to produce more and more food. At the dawn of the 21st century only 1% of our population is still employed in farming, producing the food supply for the rest of us. (This figure is somewhat skewed, since millions of other people are still employed processing the food supply, but even the combined total employed in farming and food processing is a mere fraction of what it was in 1900.)

The transition from a nation of farmers to a nation of non-farmers was inherently painful. Evolution of the economic ecosystem led to many new advancements in production efficiency. Old niches in the ecosystem were wiped out and new ones created. Nearly every decade of the past century brought an exodus of people abandoning the family farms for jobs in the city, to produce completely new goods and services. The death of the family farm was agonizing and demoralizing for every Mom and Pop and their children forced to sell their holdings to start over in this unknown new world. Change is scary in any form, especially when you are not in control of it. But if we had not changed then we would be living in something like a third-world country today.

Consider that in a developing country a farmer's entire assets may amount to ten cows. His annual surplus may consist of only five or six half-grown cows each year. Now, would you really be willing to trade a year of your hard work and effort for a year of his?

In our own country a rancher may raise a thousand cattle and produce an annual surplus of several hundred animals. Every crash in the cattle market from overproduction and under-consumption leads to the tragic death of still more family farms and consolidation into ever larger farms and ranches. Individuals hang on precariously as long as they can, until a drought or some other natural disaster finishes off their operation. But this painful process also means that the remaining ranchers will produce a greater surplus for exchange. Your wages will buy more beef than ever, and the latest ranchers to lose their lands will become employed producing new goods and services. Industrialized farming may mean that 1% of the population has to produce enough food for themselves and the other 99% of the country, but it also means that 99% of the population is working to produce goods and services for farmers!

For example, videos did not exist before the 1970's, but today there are millions of people employed in the business to manufacture, distribute, lease, and sell VCR's, videos, and camcorders, and their next generation kin, the DVD's. What were all these millions of people doing before these technologies were invented? It is hard to say specifically, but many of them would have been farmers if it weren't for farm consolidations. Increasing farm production allowed videos and many other new goods and services to enter the marketplace, giving us all access to small luxuries that our ancestors never had.

2) Increased production gives us more products and more freedom to choose, but also makes us work more. Some people talk about reducing the work week from five days down to four. They look around at the technology that allows us to produce wealth so easily, and it seems as though we are near the point where we will be able to shorten the work week. But the reality is that we have more expenses and more possessions than ever before. We talk about working less, but the truth is that more and more Americans are working longer, taking on second or third jobs just to "survive".

For young adults it is especially difficult, because they want and expect everything they had in their parents house, and they want it now. They are thrilled to get a job and start making payments on a car, a stereo system, and rent for an apartment. Pretty soon they are spending more money than they earn, yet they have little to show for it except an endless stream of bills. The decision whether to work or not is free choice, but people like all the stuff our culture produces, and they willingly sell their souls to employment to pay for it. It is only after the bill arrives that they feel buyer's-remorse, caught in a trap of forever walking the treadmill of work. Mostly I think that people don't realize they have a choice, since they've never imagined anything else. For example, many people drink soda pop every day of their lives, although our ancestors certainly never had that luxury. The minimally "health conscious" might purchase diet sodas to avoid weight gain. Now, a diet soda is supposed to be a good buy because there is only one calorie per can. However, human beings need about 2,500 calories per day for sustenance. Therefore, at 50¢ per can it would cost $1,250 per day to live on diet sodas. Clearly there is no economic incentive to buy diet sodas, but people buy items like that every day and wonder why they are broke!

One of the problems with increased production efficiency is that a smaller and smaller segment of the population is left providing for all the basic survival needs of the culture, such as food, water, clothing and shelter. When we indulge in a night of video rentals and soda pop we are in effect agreeing to work harder to provide for the people employed providing those goods and services. They are no longer providing their own food, water, clothing, and shelter, but we agree to do it for them in exchange for the luxury of a movie theater in our homes. The exciting thing is that there is no law that says we have to spend our hard-earned money that way. Each of us is completely in control over our decisions to spend or not to spend, to work or not to work. As you will see later in the book, there are many opportunities in life that you may have never considered.

3) Increased production results in a greater surplus to share with "non-producing" individuals such as government officials, nonprofit organizations, or the poor. Video rentals or soda pop are hardly essential goods and services, but increased production results in an income surplus to spend, so we do, thereby providing people in those occupations with all that they need. Similarly, think about how many people work for the city, county, state, or federal government. Each government employee may provide a valuable service to the public, but the rest of us have to work to cover their basic needs. Still, we are all a little richer with increases in production efficiency, so we can afford to pay higher taxes, some of which will be transferred to the poor, and we can afford to donate to environmental or social causes.

Greater production efficiency means there is more wealth to spread around, but it also means there is more demand for a share of the handouts. With every increase in efficiency there is a greater potential for some individuals to make much more income than other individuals, as opposed to more primitive economies where nobody has anything anyway. Giving money to the poor helps to close the gap a little bit, so that the poor are wealthy compared to our ancestors, even though they may be poor compared to mainstream society. Already we channel about 40% of our tax dollars directly from those who have money to those who do not, through programs like welfare, social security or medicaid. Individuals make additional contributions to social and environmental causes every day.

Nonprofit groups are gradually learning to capitalize on the available and abundant surplus to support their programs in big ways. For example, some non-profits have linked up with credit card companies to receive a small percentage of all sales when people use their card, or they have linked up with stores on the internet to get a percentage of sales for all the customers who pass through their gateway. With dramatic new increases in production efficiency just around the corner, we may soon see nonprofit social and environmental organizations with multi-billion dollar budgets. Unfortunately, all that money won't be enough to close the growing gap between the have's and the have-not's.

4) Increased production suggests that we will witness still more changes in the future. As we move into the 21st century we are transitioning from an industrial economy where people use machines to produce material wealth to an automated economy where computers use machines to produce material wealth. Many people would say that the booming economy and soaring stock market which started in the 1990's was the result of free-trade and the subsequent corporate exploitation of low-cost labor in China and other parts of the world. While free-trade is certainly a contributing factor, I suspect that the primary cause of the economic surge is due to increased automation.

A large portion of our trade with China and other countries with low-paid workers involves trinkets for kids meals at fast food joints and other disposable toys. Most of these items are in the garbage can within a few days of purchase. That kind of trade does not increase our wealth, but only decreases it. The main cause of the economic surge is likely from increased production due to newer and better computers.

Computers were in use before 1990, but they were expensive and didn't do very much. New computers and computer networking, especially the internet, has led to many increases in production. An obvious example is Amazon, which offers customers many more books in one store. Customers do the work of placing orders via their own computers, while Amazon's computers do the work of automatically monitoring inventory, ordering books, paying bills and routing the customer orders to the right bins in the right warehouse. Amazon sells more books with less labor, so they are able to offer discount prices on many books that you would not get through traditional booksellers.

What we will see in the coming decades is increased automation in every sector of the economy. Already there are printing services that can keep an author's books in storage on a computer and print only as many copies as are ordered. If only one copy is sold today, then only one copy is printed. Soon we may see businesses like Amazon where paper and ink is delivered and put in place, but otherwise computers do everything from taking the order to printing, packing, and dropping it in a bin for the post office. There will also be many more electronic books where computers handle every part of the transaction without human involvement. What will these kind of technologies mean for the world we live in?

Just imagine if you were a tailor and you had a computerized factory where customers picked the styles they wanted via the internet, then typed in their measurements. Computers would custom cut, sew, pack, and mail every garment without human hands. Computers would handle all the billing and ordering-maybe even the returns. There would be work to maintain the equipment and put the rolls of fabric in place, but even those jobs have the potential for automation. Instead of hand-stitching 52 complete outfits in a year, you might push the "on" button and stitch 52,000 in a day. We are already millionaires compared to our ancestors, but in the decades to come we will be millionaires again, compared to where we are now. But can this cycle keep going forever? When do we have enough?

If trends continued into the future as they have in the past, then we would expect middle class families to own at least "one space shuttle per family" in future decades. With production costs falling and wealth therefore rising, it would be the affordable family sedan-even if it still cost 1,000 times the price of a car.

Many individuals are finally saying "enough" and deciding that it would be better to slow down productivity a little bit, for example, by sending more farmers back to the land to tend small, organically grown plots. People are also realizing that they have the freedom to do something besides work and spend, so they are making new choices.

Yet the vast majority is still enamored with increasing wealth and disposable life-styles. For example, with a booming economy more middle class Americans are buying gas-guzzling SUV's and even motor boats, which once belonged only to the "rich". But is this endless pursuit of growth and material goods sustainable?

5) Increased production also seems to require increased throughput of materials and energy, and therefore causes greater ecological impact. There are advantages and disadvantages to every type of economy, simple or advanced. The hunter-gatherer economy is the most simple economic structure. It doesn't produce much material wealth, but it doesn't require much work from the people either. The land provides food, water, and fuel free for the taking, so there isn't that much work to do, and waste management is a simple as moving to a new site when the old one is a mess. As long as the population remains within the carrying capacity of the land, then the system is completely sustainable.

An agrarian economy is a slightly more advanced economic system. It provides more food from the same land base to support a larger population. Production and specialization of labor increases, and those who are not needed for farming are available to provide new goods and services that were not practical in a hunter-gatherer economy. Some new goods and services are required, such as mining for iron and forging it into plowing implements, while others are new luxuries, such as larger musical instruments that hunter-gatherer peoples could not possibly carry with them. Overall, the agrarian economy increases wealth, but leads to new problems.

One problem is that increased production requires additional inputs of resources and energy and leads to more waste and pollution. The level of environmental disturbance is much greater than in a hunter-gatherer economy, and some of the goods and services that were formerly provided for free from the environment now require human labor to provide. For example, tilling the land to plant a crop displaces the wild foods that were formerly free for the taking. Surface water that was formerly drinkable may become polluted from people and animal waste, necessitating a well. Wastes that were formerly recycled where they lay now have to be hauled away.

An industrial economy leads to similar increases in production and personal wealth, but also requires a much greater throughput of resources and energy. Like the agrarian economy, the industrial economy requires more resources and higher-quality resources, such as more refined metals. The level of environmental disturbance increases greatly, and society has to take on additional roles that were once provided for free by nature. For example, an agrarian economy may disturb some land in logging and mining, but given enough time the environment recovers on its own. An industrial economy, however, disturbs so much land that reclamation work and tree planting is required, adding more work for people. Waste management, which was once a matter of dumping garbage in the nearest ravine, takes on new complications when dealing with toxic compounds that leach back into the food and water supply. Contaminated ground and surface waters require sophisticated treatment systems to clean the water both before and after use.

Given that advanced economies require so much throughput, it may seem that creating a sustainable modern economy is simply impossible, that the fate of the planet is sealed. However, there is more to it than that. In order to get a fresh perspective on how to make the world a better place, we must first come to terms with the industrial economy, that it is here to stay and it will continue to grow and consume. As strange as it seems it is possible to support an industrial economy without consuming the entire planet, as is laid out in the subsequent chapters.

In conclusion, there is no doubt that we are wealthier today than ever before. Life is relatively easy in the sense that we do not have to work very hard for anything. We only work harder because we are working for more than we ever did before--and that is a choice we have control over. The exciting part is that advanced economies provide more opportunities to choose how we spend our time and money, though few people realize it. In a hunter-gatherer society you have little choice to be anything but a hunter-gatherer. In more advanced, complex economies you have the freedom to choose what kind of work you want to do and even how much work you want to do. As you will see, it is even possible to have a prosperous life-style without damaging the world we love!

Imagine being a tailor, one of several within a simple economy. You custom-cut and hand-stitch garments to exchange for your food, shelter, and other needs. Like other local tailors, it takes you a week to make an outfit for one customer, so your total annual production is 52 complete outfits per year. Therefore, those 52 outfits are equal in value to everything that you trade for and consume within the year. But then you get this idea, "What if I could make a device to assist with the sewing, so that I could produce more garments in less time. Then I could sell more garments and make more money, or I could take extra time off to hike in the woods."

Imagine being a tailor, one of several within a simple economy. You custom-cut and hand-stitch garments to exchange for your food, shelter, and other needs. Like other local tailors, it takes you a week to make an outfit for one customer, so your total annual production is 52 complete outfits per year. Therefore, those 52 outfits are equal in value to everything that you trade for and consume within the year. But then you get this idea, "What if I could make a device to assist with the sewing, so that I could produce more garments in less time. Then I could sell more garments and make more money, or I could take extra time off to hike in the woods."